This is an ongoing, decade by decade, attempt to catalogue in 500 words or less the most notable skinhead books, starting with Richard Allen’s Skinhead in 1970 and ending on ST Publishing’s output until the turn of the century. Click here for Part 2 – the 80s.

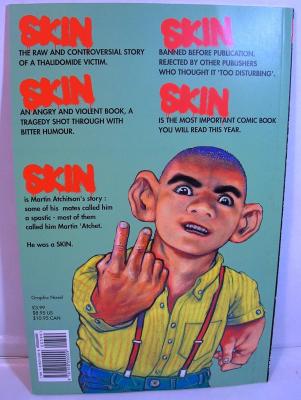

Skin

Peter Milligan and Brendan McCarthy, 1992 (Tundra UK)

Skinheads and the drug Thalidomide don’t usually feature prominently in discussions of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, but we’ll get to that later. The late 80s and early 90s were to some extent the fag-end of skinheadism before its later second wind. If the flagging fortunes and attempted metal stylings of former Oi acts weren’t enough, you only need to look at Bill Buford’s lyrical account Among The Thugs (1992) for when his newfound Millwall supporter friends become alert to the presence of an undercover journalist from the Daily Mail as “it was pointed out that no one had worn a bomber jacket and Doc Marten boots for about ten years”. Ripe for a revival or a sardonic lookback at least, skinhead found another unlikely anti-hero in Peter Milligan and Brendan Mc Carthy’s Skin, with self-declared “seal boy” Martin Atchitson (or just ‘Atchet) and his acceptance as a vengeance-seeking Thalidomide survivor in a 70s skinhead gang.

Skinheads and the drug Thalidomide don’t usually feature prominently in discussions of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, but we’ll get to that later. The late 80s and early 90s were to some extent the fag-end of skinheadism before its later second wind. If the flagging fortunes and attempted metal stylings of former Oi acts weren’t enough, you only need to look at Bill Buford’s lyrical account Among The Thugs (1992) for when his newfound Millwall supporter friends become alert to the presence of an undercover journalist from the Daily Mail as “it was pointed out that no one had worn a bomber jacket and Doc Marten boots for about ten years”. Ripe for a revival or a sardonic lookback at least, skinhead found another unlikely anti-hero in Peter Milligan and Brendan Mc Carthy’s Skin, with self-declared “seal boy” Martin Atchitson (or just ‘Atchet) and his acceptance as a vengeance-seeking Thalidomide survivor in a 70s skinhead gang.

Milligan initially tried to find a home for Martin Atchet in Crisis, one of several titles associated with the late 80s and early 90s alternative comics boom which ultimately petered out with 1995’s tanking (no pun intended) of Tank Girl at the Hollywood box office. Entirely typical of that boom, Crisis was the answer of Fleetway (the UK’s answer to Marvel or DC) to the rise of the more cerebral (and ultimately commercial) indies Deadline and Toxic.  Alongside the likes of Brett Ewins and Brendan McCarthy, an early leg-up was provided by Sounds, where Milligan’s punk surrealism found its metier. Company parted however with the unwillingness of Fleetway (by now under the ownership of pensions swindler Robert Maxwell’s Mirror Group) to carry Milligan’s Skin strips on account of their subject matter, with its printers also threatening to down tools. This was the era when Manchester press Savoy Books’ allegedly violent and racist Auschwitz graphic novel Lord Horror was relentlessly pursued by the dogged local constabulary of ‘God’s Cop’ James Anderton all the way to the country’s last Obscene Publications Act trial (the book itself inspired by real scenes of prisoners burnt alive during earlier jailings of its author for obscenity in the city’s notorious HMP Strangeways).

Alongside the likes of Brett Ewins and Brendan McCarthy, an early leg-up was provided by Sounds, where Milligan’s punk surrealism found its metier. Company parted however with the unwillingness of Fleetway (by now under the ownership of pensions swindler Robert Maxwell’s Mirror Group) to carry Milligan’s Skin strips on account of their subject matter, with its printers also threatening to down tools. This was the era when Manchester press Savoy Books’ allegedly violent and racist Auschwitz graphic novel Lord Horror was relentlessly pursued by the dogged local constabulary of ‘God’s Cop’ James Anderton all the way to the country’s last Obscene Publications Act trial (the book itself inspired by real scenes of prisoners burnt alive during earlier jailings of its author for obscenity in the city’s notorious HMP Strangeways).

It would take Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles creator Kevin Eastman’s Tundra press to finally publish Skin (touted unsuccessfully among a number of sympathetic publishers, including George Marshall’s ST operation) as one complete work on its short-lived UK arm. The story itself, unpalatable as it clearly was to mainstream sensibilities at the time, deals with (in the words of McCarthy) “universal themes of major companies shafting people, and corruption in terms of drugs and mass marketing.”  Albeit as lived through the experience of a 1970s skinhead, almost taking up the cudgels of James Moffat as Richard Allen’s critique of 60s social liberalism and discarded consequences. Shunned by society, the unlikely hero seal-boy Atchet finds loyalty among a skinhead gang like any found the literature of the period and as with Allen’s Skinhead, the penetration of a “tasty” hippy is not far away, nor with love interest skingirl Ruby (unlike Allen these acts shown in vivid colour). With Skin now out of print (as with most of the books in our series), Atchet was the subject of an affectionate tribute by midwestern hardcore band Modern Life is War. But remember, most importantly, “He was a SKIN.”

Albeit as lived through the experience of a 1970s skinhead, almost taking up the cudgels of James Moffat as Richard Allen’s critique of 60s social liberalism and discarded consequences. Shunned by society, the unlikely hero seal-boy Atchet finds loyalty among a skinhead gang like any found the literature of the period and as with Allen’s Skinhead, the penetration of a “tasty” hippy is not far away, nor with love interest skingirl Ruby (unlike Allen these acts shown in vivid colour). With Skin now out of print (as with most of the books in our series), Atchet was the subject of an affectionate tribute by midwestern hardcore band Modern Life is War. But remember, most importantly, “He was a SKIN.”

Andrew Stevens

Spirit of 69: A Skinhead Bible

George Marshall, 1994 (ST Publishing)

England Belongs to Me

Steve Goodman, 1994 (ST Publishing)

Boss Sounds: Classic Skinhead Reggae

Marc Griffiths, 1995 (ST Publishing)

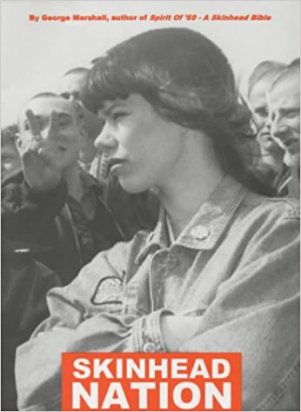

Skinhead Nation

George Marshall, 1996 (ST Publishing)

By 1994 a growing economy had forced me off the dole and I found myself a DSS (Department of Social Security, as it had become) clerk awaiting entry onto a journalism diploma. The National Express coach to London was all that stood between me, the photocopier and a return to the Giro, the occasional forays down the M1 to Merc to exhaust my £120 a week wage on Ben Shermans and printed materials. George Marshall, though I never met him, was never far from my thoughts in all this and ST Publishing’s output was well-thumbed on those return trips (his post-sussed Skinhead Times itself more easily acquired from Trev in Newcastle’s zine distro).

By 1994 a growing economy had forced me off the dole and I found myself a DSS (Department of Social Security, as it had become) clerk awaiting entry onto a journalism diploma. The National Express coach to London was all that stood between me, the photocopier and a return to the Giro, the occasional forays down the M1 to Merc to exhaust my £120 a week wage on Ben Shermans and printed materials. George Marshall, though I never met him, was never far from my thoughts in all this and ST Publishing’s output was well-thumbed on those return trips (his post-sussed Skinhead Times itself more easily acquired from Trev in Newcastle’s zine distro).

With a fair clip of enthusiastic and accessible 2-Tone histories under his belt by that year (in an era when the Selecter were wearing shellsuits and Bad Manners derided as a novelty act, not to mention the debacle of Madstock), Marshall valiantly kept the home fires burning with not only Skinhead Times (self-declared as “neither red or racist” but having a side picked for it) but also his bootboy “Bible”, the Spirit of 69, so-named to distinguish it from the indelible associations by that point of skinhead with the bonehead nazis he was trying to give a wide-berth to.  Like Nick Knight before him, Marshall assembles press clippings and ads, his own numerous potted histories of skinhead subculture (“urban jungles”) and style, taking in Richard Allen, the Paint House and Sham Army dispatches from his native Scotland, appendixed with streetwear and reggae imprints (enabling the reader to name-drop all 57 varieties of Trojan at their next dance). Slightly uneven, with an almost blow by blow account of the lesser-known mini riot at 1984’s Great Yarmouth scooter rally caused by actual fascists (what kind of lowlife punches Desmond Dekker on stage?), it was followed by the more anecdotal Skinhead Nation, which perhaps goes some way to demonstrate how stateside it was all by the mid-90s.

Like Nick Knight before him, Marshall assembles press clippings and ads, his own numerous potted histories of skinhead subculture (“urban jungles”) and style, taking in Richard Allen, the Paint House and Sham Army dispatches from his native Scotland, appendixed with streetwear and reggae imprints (enabling the reader to name-drop all 57 varieties of Trojan at their next dance). Slightly uneven, with an almost blow by blow account of the lesser-known mini riot at 1984’s Great Yarmouth scooter rally caused by actual fascists (what kind of lowlife punches Desmond Dekker on stage?), it was followed by the more anecdotal Skinhead Nation, which perhaps goes some way to demonstrate how stateside it was all by the mid-90s.

Referencing the newly resurgent Cock Sparrer’s signature tune of a decade before, England Belongs to Me was ST’s attempt (as Low Life) to similar new life into NEL-style pulp, along with the more pedestrian and even more predictable Saturday’s Heroes and Casual (having turned down Peter Milligan’s Skin).  As rudeboy referencing goes, it’s a title which could only ever appeal to the ST completionist in you, after you’ve burned your own wage packet on pricey editions of Richard Allen, a writing-by-numbers formulaic tale of skinhead meets punk girl and defeats nazi gang leader along the way (that 70s milieu more deftly handled since by the likes of Max Schaefer’s Children of the Sun). The limited impact of this run of pulp pastiche, published on probably the most reputable imprint since the NEL itself, has not deterred others in its wake. You would, however, be very hard pushed to find anyone with a bad word to say about Boss Sounds (the racist skins in England Belongs to Me, perhaps), which ranks as pretty much the first and last word on skinhead reggae in print. In an era in which skinhead has gained more media and subcultural acceptance than in preceding decades (ask today’s 20 year-olds in pristine suedehead clobber), where new Richard Allens can sell out print runs following a Don Letts documentary, a reprint is overdue but probably unlikely. Over to you again, George.

As rudeboy referencing goes, it’s a title which could only ever appeal to the ST completionist in you, after you’ve burned your own wage packet on pricey editions of Richard Allen, a writing-by-numbers formulaic tale of skinhead meets punk girl and defeats nazi gang leader along the way (that 70s milieu more deftly handled since by the likes of Max Schaefer’s Children of the Sun). The limited impact of this run of pulp pastiche, published on probably the most reputable imprint since the NEL itself, has not deterred others in its wake. You would, however, be very hard pushed to find anyone with a bad word to say about Boss Sounds (the racist skins in England Belongs to Me, perhaps), which ranks as pretty much the first and last word on skinhead reggae in print. In an era in which skinhead has gained more media and subcultural acceptance than in preceding decades (ask today’s 20 year-olds in pristine suedehead clobber), where new Richard Allens can sell out print runs following a Don Letts documentary, a reprint is overdue but probably unlikely. Over to you again, George.

Andrew Stevens

You missed the book Skinhead Girls

LikeLike

As in the ST omnibus of Richard Allens? It’s collected 70s novels already discussed

LikeLike

I think Anonymous means the 1988 photo book, ‘Skinhead Girl’. Really hard to find.

LikeLike

But it’s the 90s

LikeLike

Interesting to read about all of this stuff after my time but it leaves me a bit cold to be honest. Then again so does Richard Allen, Nick Knight for the win! That 1988 Skinhead Girls book sounds good though.

LikeLike

Pingback: Le origini del termine "bonehead" – Crombie Media

Pingback: Classic skinhead books: 1970-2000 – Crombie Media Blog