This is an ongoing, decade by decade, attempt to catalogue in 500 words or less the most notable skinhead books, starting with Richard Allen’s Skinhead in 1970 and ending on ST Publishing’s output until the turn of the century. Click here for Part 1 – the 70s.

The Story of Oi! A View from the Dead End of the Street

Garry Johnson, 1981 (Babylon Books)

Oi poet (and later Stone Roses manager) Garry Johnson’s 1981 book has long been out of print, and even a 2008 reissue now sells for £100 on Amazon. To be honest, it isn’t really worth that kind of money, so we’re making it available as a PDF download. Babylon Books are no longer in business, and even if they were they wouldn’t stand a chance against our expensive lawyers.

Oi poet (and later Stone Roses manager) Garry Johnson’s 1981 book has long been out of print, and even a 2008 reissue now sells for £100 on Amazon. To be honest, it isn’t really worth that kind of money, so we’re making it available as a PDF download. Babylon Books are no longer in business, and even if they were they wouldn’t stand a chance against our expensive lawyers.

1981 Garry Johnson – Oi! A View From The Dead End Of The Street

The book partly tries to establish a cultural canon for the Oi generation, according to the author the “first real street movement since the original skinhead cult”. Hence, some chapters are like extended versions of Bushell’s liner notes for the first few Oi! albums. The reader is introduced to the definitive Oi group, the 4-Skins, in some detail. There is a pretty ropy account of late 60s reggae (Judge Dread is cited as a ‘ska favourite’ of the original croptop era), and a picture of Australian post-sharpie rock combo Rose Tattoo implies that they’re somehow part of it too – if not physically or musically, then at least in spirit. “Oi Oi Aussies”, reads the caption.

Yet because it was published a mere few months after the Southall disaster, much of the book reads like the author wrote it with his back against the wall. Johnson is on the defensive, lashing out at Tories and Labour, SWP and NF. Every outsider to Oi who doesn’t outright wish to “crucify the skinheads” – to cite an unconfirmed Thatcher quote – stands accused of using or at least patronising them. While the stiff-arm brigade is damned to hell, Johnson’s identity politics depend more on railing against Islington do-gooders, social workers and champagne socialists. Ironically, the official organ of latte liberalism, The Guardian, was the only paper to give Oi a fair hearing after Southall, while pseudo working class rags from The Sun to Socialist Worker screamed for the witch trials to commence.

What’s striking is how similar the views voiced by Johnson were to those in the much maligned Crass/hippie punk camp. “Politics” left and right only stop you from “thinking for yourself”. All politicians are “the same”. Organisations just want to “use the kids”. And so on.

What’s striking is how similar the views voiced by Johnson were to those in the much maligned Crass/hippie punk camp. “Politics” left and right only stop you from “thinking for yourself”. All politicians are “the same”. Organisations just want to “use the kids”. And so on.

If your worldview has never evolved beyond this basic outlook you should probably start “thinking for yourself”, yet at least Johnson is no earnest peace punk passing this off as philosophy. Moreover, there’s an immediacy to The Story of Oi (about which we learn very little, by the way) that makes it one of the most authentically ‘punk’ documents of its era. Johnson’s poetry, some of which is contained in the book’s pages, would vastly improve a couple of years later.

Crombieboy

Oi for England

Trevor Griffiths, 1982 (Faber and Faber)

“There’s nothing here for me and you / Not in 1982”

“There’s nothing here for me and you / Not in 1982”

– ‘1982’, Combat 84

Forget the events of May 1968 or even all the skinheads standing in a line a year later, 1982 ranks as the year of ‘UK82’ street punk and skinhead dramas Made in Britain and, also shown on ITV, Oi for England. It is included here as the play’s script (intended for and used by community theatre groups) was published by Faber and Faber that year.

Written in response to the events of 1981, both the inner city riots of Brixton, Handsworth and Toxteth as well as the Hambrough Tavern in Southall, Trevor Griffiths’ Manchester-set play deals with four short-changed members of skinhead band Ammunition as they contend with not only a far-right concert promoter looking to (in the Martin Webster vein) co-opt their frustration and physical presence but also their lack of unity as a group on where this fits in with their situation amid early 80s Britain (the dole, police brutality etc.)

Set entirely in the band’s basement rehearsal space (the black landlord and his daughter, also a character, providing a further dimension), the play itself largely consists of the dilemma brought by ‘The Man’ (the unnamed character played by Gavin Richards, almost channelling Geert Wilders, in the TV adaptation) and the tensions between Ammunition’s members (who must play as ‘White Ammunition’ if they’re to get a slot at the ‘skinfest’).

Griffiths himself, as perhaps shown by the play and its approach, was a Manchester-based teacher turned playwright, emerging in the New Left firmament of the sixties, belonging to that now extinguished northern-leftish social realist public broadcasting tradition of Barry Hines, Tony Garnett (who first commissioned Griffiths at the BBC) and Alan Clarke. Oi for England, as well as the later Iraq-themed The Gulf Between Us (1992), was acclaimed for Griffith’s commitment to staging political theatre for regional audiences (at a time when his peers were relegated to Hollywood schlock and ads for McDonald’s).

The writer’s anti-racism and the play’s Brechtian intent to provoke its intended teenage audience against real-time overtures of the far right at the school gates and on the terraces (Griffiths’ idea originating from his attendance at a conference on Race in The Classroom) is abundantly evident, to the point that writing about the play can only weigh up its subcultural heft instead. The touring version of the play was, post-broadcast, shorn of some dialogue and given extra Oi songs, which probably made it more palatable to the audience when staged as the ‘support’ at a 4-Skins gig in Keighley.

The skinhead provided a handy hook for 1980s television, beyond referencing Southall and their crucifixion by Thatcher herself, for instance, 1984 drama The Treatment, the ongoing hassles of Adrian Mole, Johnny Jarvis and Tucker Jenkins at the hands of Barry Kent, Manning and Ralph Passmore, or the general walk-on roles in the likes of Pete Townsend’s White City (1986). While Made in Britain (also produced by Margaret Matheson at Central Television) at least has a DVD release, central anti-hero, and subculture fanbase, Oi for England instead remains staged for theatre audiences (unlikely to contain many skinheads) to this day.

Andrew Stevens

Skinheads

C. Ryan, 1981 (unknown)

Skinhead

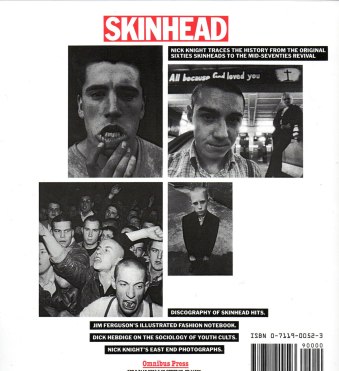

Nick Knight, 1982 (Omnibus)

Just over a decade in and skinhead had jumped from sociological enquiry to the coffee table, where (hoolie lit and pulp pastiches aside) it’s largely remained ever since (although not many skinheads owned coffee tables in the early 80s). It’s easy to see how mainstream publishing and an early career fashion photographer (still learning his craft at an art school on the south coast) however could visualise the potential afforded by a nascent teenage subculture, tugging on the ragged coat-tails of a more obscure collection.

There’s a scrappy, almost samizdat-like quality to C. Ryan’s Skinheads, of the two books here the lesser known yet possessed of its own modest charm (Knight’s containing a snarling self-portrait of the photographer as “immersed” grade 1 among the face tats and crombies). While there’s no knocking what Knight achieved with Skinhead (still in print and on the shelves, if not venerated in certain quarters), Ryan does without the state of the nation meditational essayism by Dick Hebdidge and simply lets the pictures tell their own story. Photo booth grimaces and sudden group shots simply look the business, though Knight admittedly has the iconic edge.

Where Skinhead (which at least carries the New English Library’s covers of the same title in among its own essayism and potted histories) works is the assemblage of these fragmented accounts alongside the winning and arresting shots of the embedded artist within the subculture. Knight tells us this is not an attempt to “record the truth but a truth” (as did The Paint House), yet he was not acting alone at the time, even if the likes of Derek Ridgers and Gavin Watson would take a few years yet to get their own recorded truth published (both with the benefit of a decent look-back rather than immediate post-Hamborough Tavern reportage).

Where Skinhead (which at least carries the New English Library’s covers of the same title in among its own essayism and potted histories) works is the assemblage of these fragmented accounts alongside the winning and arresting shots of the embedded artist within the subculture. Knight tells us this is not an attempt to “record the truth but a truth” (as did The Paint House), yet he was not acting alone at the time, even if the likes of Derek Ridgers and Gavin Watson would take a few years yet to get their own recorded truth published (both with the benefit of a decent look-back rather than immediate post-Hamborough Tavern reportage).

Knight also tells us that the signs of decline were already there as he began his project, with London’s pubs and clubs increasing calling time on skinheads’ presence in their licensed premises (as he mentions, ‘Squires’ in Catford being the last among the South London constellation which included a skinhead disco in nearby Grove Park – o tempora, o mores!). After this all bodies descended on the Last Resort on Goulston Street as the focal point and retail hub, Knight recording his thanks to gainful opportunistic proprietors Margaret and Micky (without whom there’d clearly be no book). Naiveté in itself often ranks as charm and while the book’s reputation is for the shots of the tribe, buyers probably got as much out of the prescriptive (or “fanatical”) listicles of classic skinhead records (which claims to have “ignored the most obvious”, with ‘54-46’ his number one), hair and sideburn lengths or simply how to dress.

For all the talk of an “ugly” and maligned youth cult viewed as “trouble” for its racist element, there’s several shots of black skinheads in Oi get-up (presciently given that Knight would later direct Kanye West’s own ‘Black Skinhead’). And in later years, Knight would also go on to trouser an OBE for “services to the arts” and even receive a commission for the Queen’s 90th birthday in 2016, taking his earliest subculture photography to solo exhibitions as far afield as Seoul. C. Ryan remains a more unknown quantity and whether Knight likes it or not, probably retains some sympathies and admiring glances along the way.

Andrew Stevens

Next: the 90s

Pingback: Skinhead Classics: Books for Bootboys 1970-2000. Part Three – the 90s – Creases Like Knives

Pingback: Classic skinhead books: 1970-2000 – Crombie Media Blog

Alan Mead’s book “Skinhead Girls” was it…….garnishes large amounts of money now and was a good pictorial view of the skinhead style.Unfortunately its popularity led to my copy being nicked.I think he was from down Bristol or Avon way????

LikeLike

Who is/was C. Ryan? Was he an skinhead? Is his book the first “in-scene” book?

LikeLike