First things first: Stevo originally did this interview in 2010 for another website, but he figured there’s no harm in reprinting it (with permission) here, as the book and author haven’t really been heard of since.

Children of the Sun was the debut novel of Max Schaefer, acclaimed when it was published in 2010 for its methodically well-researched tackling of 80s South London nazi skins, Nicky Crane, and the bizarre dabblings of the more well-heeled members of the far right.

The book’s journey through the world of fascist microsects, homosexuality and the occult is bound to confuse your average ‘bonehead’, but makes for a captivating London novel. And unlike is the case with much ‘skinhead literature’, the author’s eye for detail is impressive: for once, this includes accurate skinhead dress codes from 1970 through the late 80s.

Text: Stevo

Children of the Sun has been widely reviewed on what we might call the far left, but are you aware of any specific reaction from those the book covers, namely the far right? I take it you didn’t invite Nick Griffin to the book launch?

Children of the Sun has been widely reviewed on what we might call the far left, but are you aware of any specific reaction from those the book covers, namely the far right? I take it you didn’t invite Nick Griffin to the book launch?

I’m not aware of any reaction whatsoever on the far right. I’m trying not to feel hurt…

No invitation was extended to Griffin. In fact, one of the decisions I made early on was that the research would not extend to making contact with any such individuals. Given the ton of neo-nazi material I had to work from, not to mention secondary sources, it didn’t seem necessary, and I felt it might compromise the project (not to mention me) in a range of ways. Besides, avoiding personal contact seemed pretty consistent with the plot and structure of the book overall.

The title appears to have given rise to some confusion as to its origin, Stewart Home, for instance, pondering 60s psych classics, but it’s actually derived from post-war nazi occultist Savitri Devi. Can you say a little on why you chose it?

The title appears to have given rise to some confusion as to its origin, Stewart Home, for instance, pondering 60s psych classics, but it’s actually derived from post-war nazi occultist Savitri Devi. Can you say a little on why you chose it?

It wasn’t my original choice. The working title for the book was Ian & Nicky, but while it had the support of a few writer friends, my agent and publishers hated it — as, to be fair, did most everyone else I happened to ask. Finding a title we could all agree on was an extended process (and one during which Granta couldn’t have been more patient).

I’d tried a few times to come up with alternatives, including trawling through the manuscript for likely phrases, during which I considered and rejected Children of the Sun among several others. My main concern was its over-familiarity, both per se and for the other titles it echoes.

But then my agent suggested it independently (on the basis that beyond the direct neo-nazi reference you mention, it ‘captured the lamentable vainglory of these people but also their sympathetic innocence’, as well as refracting on James, the young researcher in the present-day strand of the narrative), and while we continued to discuss several others, Children was the one that stuck. It has grown on me.

I suppose I should ask then, why Nicky Crane?

I hope the book might answer that at least in part… I first became aware of Crane when a friend mentioned him over dinner, and the obvious contradiction in his life made me curious enough to start some research — I thought he might make a good short story. But the research quickly became a lot broader. So he was an entry to the subject for me, and he performs a similar function in the book.

You use the life and death of Crane as a device for the book, both in the retelling of the past and the more recent present. Regardless of his crimes and actions as part of the far right, did you ever pause to think about what effect this might have on those to whom he was a son, a brother etc?

I thought about it, but to be honest I didn’t pause for very long. For a start, there’s no information about him in the book that wasn’t already publicly available, with the possible exception of the date and place of his death. Moreover, Crane himself talked very publicly about his sexuality and his nazi past — he did it on TV, and in The Sun. And in the end, there’s very little of Crane in the book; he’s as much an absence as anything else.

It’s interesting that you ask that question specifically about Crane when several other real people appear, or are mentioned, in the novel. Was there something about how he’s treated in particular that made you uncomfortable?

Well, no, but it was more the fact that he’s dead. In the book there’s both your text as story and the introduction of clippings of the era borrowed from a number of sources, which punctuate between chapters. One of which shows how Searchlight constantly sought to out Crane while he was an active member of the more militant end of the far right. Do you think those around him were really oblivious to it, despite this, or if it was more convenient for them to turn a blind eye to it?

Well, we know the far right has happily accommodated other people whose sexuality was an open secret — such as Martin Webster. And one thing that’s clear is they can’t have been oblivious to what Searchlight was suggesting, however they responded to those suggestions. In fact, Ian Stuart admits as much in one of his last interviews, which we reproduce in the book: “I used to stick up for [Crane] when people used to say he was queer”.

So it’s not denied people used to make those claims — Stuart merely refused to believe them, or at least to say he did. And the question becomes what’s at stake in such claims of knowing, or not-knowing, or knowing-that-not (and who’s making those claims, about whom and to whom)… which is the sort of thing Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick wrote about brilliantly and at length, and won’t boil down to a simple either-or.

An obvious point: nobody disputes that Crane was about as hard and violent as skinheads got. If you were a nazi comrade of his, would you want to be the one to confront him?

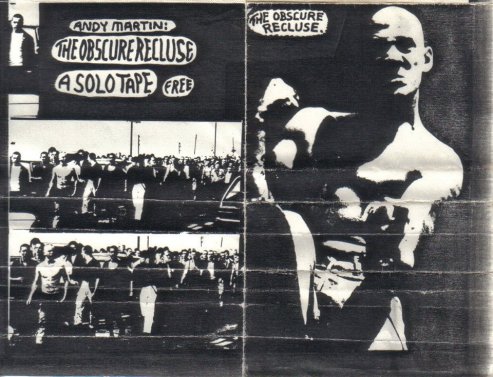

The use of the clippings follows a certain trajectory, where you show how the Blood & Honour scene evolved from almost apolitical street punk to full-on Rock Against Communism. At certain points, Mensi of the Upstarts, a noted anti-fascist, is almost swept up in it in response to the antics of the liberal left and its treatment of working-class youth. Was this deliberate?

The clippings had a couple of obvious functions. One was to provide some level of background information to readers less familiar with context than, say, you — particularly once I’d got rid of James’s journalism, which performed a similar job but did rather drown things. My hope with the clippings was that as they’re somewhere between image and text the reader would feel freer to skip them if s/he wanted to. So in that context I certainly wanted them to tell at least some of the story of how Blood & Honour evolved.

I think that at the outset there were two things going on fairly separately. One was Skrewdriver’s career, and as you say they did start as a pretty apolitical (other than being dutifully ‘rebellious’) punk group. The other was Rock Against Communism, which was a staggeringly literal response by the fash to the success of Rock Against Racism. RAC was a statement of intent before it was a real music scene — they kept announcing its arrival, and hoping to find some bands to make it happen.

Ultimately those two things converged, because Skrewdriver were a failure and Ian Stuart reinvented the band as a big fish in the tiny nazi pond. But for a long time, he was refusing to have anything to do with RAC or the National Front, at least publicly, because he was holding out for more mainstream success. I guess it’s a pathetic, tiny version of the old cliché: if Hitler had sold more paintings… except that there was nothing unique about Skrewdriver; if they hadn’t done the job something else would have come along. The fact they’d had a sort of career before they turned nazi made them easier to sell, of course.

Besides background info I hoped the clippings would add their own colour and immediacy, as artefacts rather than descriptions of the subculture. And if you’re paying ridiculously close attention they also relate to the way James’s own research and theories end up heading, and bounce off the text of the novel in a few ways. But that’s closer attention than I realistically expect the reader to pay.

The book’s title aside, it dwells quite extensively on the role of occultism within far right circles, which generally isn’t something the wider public associates with nazi skinheads, though the bulk of the music scene’s fanzines do tend towards Celtic and Norse mythology for their titles. Why did you feel the need to dwell so extensively on this aspect of the subculture?

I suppose because it is part of the subculture, but as you say hardly the first people think of. Lunatic occult beliefs were very deeply rooted in the Third Reich itself — in the whole myth of the Aryan race, for a start — and they’re very present in neo-nazi discourse as well. One tends to rationalise this stuff, and of course I wouldn’t for a moment deny the socioeconomic context, but the nazi occultists are far from a little group off by themselves, whom the mainstream will have nothing to do with. Colin Jordan and John Tyndall both associated with Savitri Devi; Combat 18, the ur-thugs, put her on the cover of one of their magazines. Order of Nine Angles material turns up in Scorpion, the closest thing the British far right has to an intellectual journal. And so on.

Beyond that, of course, it has a narrative function, in terms of James’ trajectory.

I suppose any discussion of homosexuality and the far right can’t avoid the curious life story of Richard Barnbrook, who started out as an acolyte of Derek Jarman at the Royal College of Art in the 1980s (making ‘art films’ like HMS Discovery) but more recently has come to prominence as pretty much the second in command of the BNP as its London Assembly Member and Barking ‘organiser’. Scope here for fictional dissection or just a curious footnote in the as ever bizarre goings-on of the far right?

I don’t think I’ll be attempting a fictional dissection of Barnbrook myself — the fact that he crossed paths with Jarman is the most interesting thing about him. Beyond that he’s a fairly lousy politician: his group of councillors in Barking were thrown out wholesale in the last election, by which point he’d already been suspended for making false claims, and he now seems to be on the losing side of some factional squabble within the party. Martin Webster’s allegations about Griffin are just as notable if you’re looking for that kind of thing, but even if they were true, I have no great desire to claim Griffin for the team.

I guess the other thing Barnbrook demonstrates is how close artistic subcultures, including queer subcultures, have come to fascism over the years. If you want to play six degrees of separation from Jarman to Griffin, he’s probably the winning move but hardly the only one. You could go via Psychic TV to Coil to Current 93 to Tony Wakeford, who used to be in the Front. Or via Marc Almond, who was apparently initiated into the Church of Satan by Boyd Rice, who also worked with Current 93. Or straight from Psychic TV to Nicky Crane, who appears in their ‘Unclean’ video. Or use Stevo Pearce, whose brother ran the Front alongside Griffin in the ’80s. Or Richard Moult, or … well, you get the picture.

One review speculated that Thomas Pynchon could be an influence, but what reading up had you done on previous literature that covers the far right, for instance, Richard Allen, Dougie Brimson or John King?

One review speculated that Thomas Pynchon could be an influence, but what reading up had you done on previous literature that covers the far right, for instance, Richard Allen, Dougie Brimson or John King?

I certainly read Richard Allen, but he doesn’t do Richard Allen as well as Stewart Home does Richard Allen. I’d read Home first, and so when I got round to him Allen just seemed like Home-doing-Allen minus all the qualities Home had added — like political intelligence, and jokes.

With King, of course, I was interested in how he covered the far right, but I particularly wanted to see how he handled violence. There are a couple of big set-piece fight scenes in Children, between the skinheads and the anti-fascists, and I hadn’t written that kind of stuff before. King turns out to write fights in an impressionistic way, building things up through fragmentary glimpses and sensations. I realised I needed to be more systematic — more Muybridge than Monet — perhaps because I was writing far from my own experience, or perhaps just as a matter of taste: certainly in cinema, I’ve always preferred action sequences shot and cut in such a way that you completely understand how they play out in time and space — think Peckinpah or Woo, even De Palma, versus post-MTV montage.

I’m not sure I ever read Dougie Brimson, but I did read a bunch of non-fiction books by (or ghosted for) other sometime faces: people like Steve Hickmott and Chris Henderson. Hooligan memoirs are their own sub-genre, hovering somewhere around true crime. Most of the books I read were pretty dreadful, but they certainly helped.

You manage to tip-toe around various locales in London, be it 1970s Plumstead, the wind against concrete of Kidbrooke Estate or more recent Soho.

In earlier drafts of the book, instead of clippings, I had excerpts from James’ work: there was for an example a very detailed 10,000-word history of the early days of Skrewdriver, which I ended up cutting out entirely. But I did need to go through at least a good proportion of that research process, because as I say I was hardly writing from personal experience, and so it was a scaffold I had to have in place to build the novel, even if I took much of it down when I was done. And there’s still a great deal of precision in what happens when and where. There’s a line in the book where Tony’s hungry near Victoria, and somebody says: ‘There’s a Burger King opposite the tube entrance, or a Casey Jones in the station.’ That’s 45 minutes or so of research right there.

The anti-fascist combatants in the book are portrayed sympathetically, again how did your treatment of them weigh on your mind as perhaps a countervailing moral force to the actions of the nazi contingent?

It’s interesting you say that. Certainly, my own sympathies were very much with the anti-fascists, but with one exception they don’t really have a voice in the book; you see them entirely through the eyes of Tony, my nazi protagonist, when he’s fighting them. I didn’t go to any deliberate lengths to make them sympathetic — my general approach was to show what characters said and did, and trust the reader to respond to that rather than editorialising — but perhaps my feelings about the anti-fascists (which boil down to a recognition that fascism in the UK has historically been most effectively stopped on the streets) came through somewhat. The Remembrance Sunday fight, and the Battle of Waterloo, drew heavily on accounts by some former members of AFA, so those sections do arguably give an anti-fascist version of history.

That’s 5 minutes i’ll Never get back,pure,unadulterated clap trap

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Classic skinhead books: 1970-2000 – Crombie Media Blog

Pingback: Snapshot | Ed X's cultural highlights - the PRSD